"I decided to find out what happens to those children when their parents die”

- LAFA Team

- Dec 29, 2016

- 11 min read

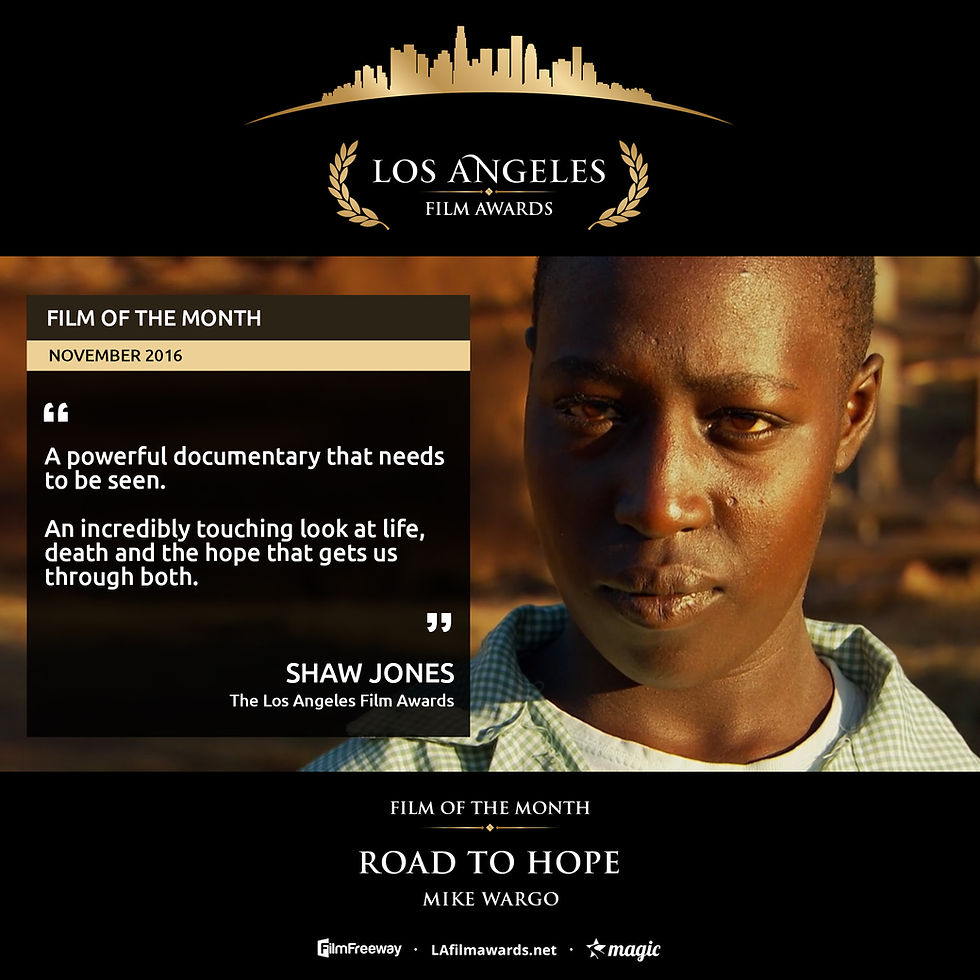

Road to Hope is an extraordinary film and the first documentary to win the Film of the Month award at LAFA. Our lead judge, Shaw Jones, described it as "an incredibly touching look at life, death and the hope that gets us through both." We interviewed director Mike Wargo, to hear the details of the exceptional story behind the creation of the film.

Watch the Official Trailer

You were a founding member of the Hospice Foundation, which is an incredible organization. How did you first get into non-profit organizations?

I was fortunate to have had some great mentors who served as role models for me very early in life. When I was in college, I was involved in student government and served as student body president in my junior year and then as editor-in-chief of my college newspaper as a senior. I learned a lot from those volunteer opportunities and concluded that volunteerism was a no-cost, low-risk way to get some great experience that could benefit me in the future. Early in my professional career, I worked for a community bank where all the bank’s officers were required to be involved with at least one community-based non-profit organization. It was just part of the culture and it’s become something that I just do without even thinking about it. I have a tough time saying “no” – particularly when there is a great cause involved. I’ve been continuously involved in various non-profit organizations ever since. I served on the board of our local non-profit hospice organization, Center for Hospice Care, for many years. As the knowledge of and demand for hospice services was increasing, we began to recognize the need to begin raising significant funds to better serve the needs of our patients and their families, both now and in the future. So, we started our Hospice Foundation back in 2007.

Why did you decide to create Road to Hope?

I produced a documentary film back in 2010 called Okuyamba, which is the Lugandan word meaning ‘to help.’ The film follows the work of specially trained nurses caring for patients dying deep in the villages of Uganda, where there is one physician for every 50,000 people. Viewers learn during the film that the life expectancy is 52 and the median age is 15 years, which is the lowest median age of any country in the world. Near the end of the film, one of our subject matter experts, Dr. Carla Simmons, talks about the fact that children are very often the primary caregivers for their dying parents. During post-screening Q&A sessions, I was continually being asked: “What happens to those children when their parents die?” I was never able to come up with a good answer to that question, so I decided to find out – and the concept for Road to Hope was born.

After a 20+ year career in the business world, what was it like for you to wear a filmmaker's hat?

It had been a long time since I’d picked up a movie camera and I’d never worked with any modern filmmaking equipment, so it was as if it was all very new to me all over again. My big birthday present when I turned 10 years old was a Super 8 movie camera and projector. I wandered all over the neighborhood shooting whatever looked semi-interesting, which got boring very quickly. I came up with an idea for a vampire movie – I was definitely ahead of my time as it was just 1970. I had a couple sets of those plastic dime store vampire teeth and a tube of fake blood. My Aunt Mary was a seamstress, so I got her to make me a Dracula-style cape. Take that, add a little make-up, and voila my friend Timmy became a vampire and star of my first silent movie. I eventually accumulated several rolls of undeveloped Super 8 cartridges, so the first thing I needed to do was save up to have them developed. Once I got the tapes back from the drug store (at a whopping three minutes each) I realized I had no way to cut them up and put it all back together. Enter the big birthday present for my 11th birthday – a Sears Du-All 8 Motorized Edit-Viewer. Though I haven’t used any of it for more than 40 years, I still have all that equipment. Who knows? Maybe someday I’ll make another silent movie.

Documentary filmmaking usually takes years... Could you share how long did it take to bring the movie to life?

I initially came up with the concept in early 2012 and wrote a treatment that I circulated among some people I knew and trusted, including Ted Mandell, who teaches in the film school at Notre Dame and with whom I co-directed Okuyamba – which is the film that sparked the idea for Road to Hope. I got some good feedback and made a few adjustments and put it in a drawer for a couple of months to gestate. I had met Torrey DeVitto, who’s currently starring in the NBC series Chicago Med, at a screening of Okuyamba in Washington DC. She liked the film and suggested I come to LA to screen it at UCLA’s James Bridges Theatre. Torrey hosted the screening, which was well received. Once again, we received questions about what happens to these child caregivers after their parents die. Torrey was interested in finding the answer as well and eventually agreed to be involved in the project. I pulled the treatment out of the drawer and began putting together a film crew. We went to Africa to begin filming in August 2013 and our DP made a couple of additional trips back during the next year to get pick-up footage. We also filmed a portion of Road to Hope in Los Angeles. Two members of our Africa film crew, Marty Flavin and Collin Erker, accompanied me to film there and both wound up moving to LA shortly after they completed their work on Road to Hope. Collin is now at Dreamworks Animation. Marty went to work for CBS and is now at the NFL Network. In all, post-production took about 14 months. We finally had a finished film in September 2015 and it premiered at the Hollywood Florida Film Festival in February 2016, where we received our first win for Best Documentary Feature. To get back to the question at hand, it took us about four years to get this film made.

How long were you shooting in Uganda? Did you need any special permits to shoot in several locations?

We shot the initial footage for Road to Hope in three different African countries over a span of about 3½ weeks. In retrospect, we probably should have had permits to film in some of the locations we ended up, but were never able to get straight answers about any specific requirements during our pre-production preparation. So, we went in without. Our film crew arrived in Kampala, Uganda in August 2013. We shot there for a few days and then made our way to Kipkaren, Kenya and then back to Kampala by way of Tororro and Jinja. After filming in the Kampala slums, we headed north to Gulu for a night and from there entered South Sudan to film in Juba and Yei. We made our way back to Uganda and filmed in a number of locations: Arua, Murchison Falls, Hoima, Kibaale and other locations – all without any special permits.

Did you work with local crew members? What was the communication like?

Since Uganda and Kenya are former British colonies, English is widely spoken among the educated and in the more urban areas. That said, communication gets a little tougher when you move out into the more rural areas. For instance, in Uganda alone there are 57 spoken languages. Our location manager, Denis Kidde, who works as the international programs coordinator for our Hospice Foundation here in the U.S. is a native Ugandan, so we had him along with us for the entire film shoot, which made communication with non-English speaking people much easier – at least in Uganda. And our Uganda-based driver, Mugisha “Owen” Muhammed, was our driver when we filmed Okuyamba back in 2010. So, he’s an old trusted friend. In addition to Lugandan, he also speaks Swahili and knew enough Arabic to get us by while we were in South Sudan. We also had Rose Kiwanuka, who is the country director for the Palliative Care Association of Uganda, with us for the last half of the shoot. She is one of the principal characters in the film and speaks seven languages, so we were well covered from a communications standpoint.

What were the most challenging moments during the shooting of Road to Hope?

I’d have to say that our most challenging moments came during our time in South Sudan. We filmed in the capital city of Juba and then made our way across some really treacherous terrain to eventually arrive in Yei, which is where we met Pastor Stanley LO-Nathan and filmed at his New Generation Dreamland Children’s Home. None of us ever got comfortable during the few days we spent in that country. The entire time I was there, I had this strange feeling that something bad was about to happen. The people were very tense. At one point, we were actually threatened by a machete-wielding villager because we came a little too close to his “driveway.” The military was on high alert and we came very close to having our camera equipment impounded when we happened upon an army barracks that looked like any other thatched hut civilian village. Police checkpoints were everywhere and we were more-often-than-not expected bribe our way through to gain passage. It was just a couple of months after we left that the country broke out into a very nasty civil war, which is still raging today. Tens of thousands of people have been killed just during the past couple of years, with boys being forced to enter the fight and young girls taken as sex slaves for the soldiers. Fighting got so bad around Yei that Pastor Stanley had to abandon the children’s home he’d founded several years ago. He fled to Northern Uganda along with his family and the scores of orphaned children in his care and is now trying to figure out their next move. It’s a very sad situation.

Road to Hope is relatively short for a feature film. Clearly, you had more footage than you actually show in the final version. Can you tell us about the editing process?

We had about 70 hours of footage from our initial shoot in 2013 and then subsequently accumulated another 30 hours, or so. In all, the footage took up about 6TB of hard drive space. Our DP, Timothy Wolfer, also served as the principal editor of the film. He was living in Grand Rapids, Michigan at the time and I was in Mishawaka, Indiana. So, we were actually about two hours’ drive time away from each other. We cloned the hard drive, so he had one in his studio and I had one in mine. We used Adobe Premiere Pro as our editing platform. Every few days, Tim would send me a link to our shared Drobox folder. I would download the latest cut, make my suggested edits, and then shoot it back to him via Dropbox. Once we had picture-lock, we sent the files to our colorist, Jonathan LaPointe, who lives in Berrien Springs, Michigan and to our ADR mixer, Stephen Tibbo, who lives in Los Angeles. Jonathan and Steve were very quick in their turnaround time. Johnathan had set aside time to work on our project and Steve was on hiatus from his day job on ABC’s Modern Family. Tim and I were both working on other projects, which is one of the primary reasons post-production took so long. In all, we wound up with just over 100 cuts to make our little 71-minute film.

A film such as Road to Hope, shot in Africa, presents some 'bonus' challenges in post-production.

We were fortunate to have Denis Kidde, a native Ugandan, on our team. He could translate almost all the footage we shot in Uganda and his wife, Grace Munene, who is a native of Kenya, was able to handle the Swahili. Once we’d identified all the usable footage we thought we may be able to use, we gave the digital files to them and they transcribed them for us using the embedded timecodes. That said, there were certain dialects that neither of them could make out. Between the two of them though, they know a lot of people in our local area who are from Uganda and Kenya and were able to find someone to translate what they couldn’t, including the Arabic spoken in the footage we shot in South Sudan.

What was the process behind the score for this film? How did you find the composers, how did you work with them?

Two days before we headed to Uganda for the initial shoot, I ran into Marvin Curtis, a composer friend of mine, in the parking lot of our local dry cleaner. He asked what I’d been up to and I told him about our film project. He then asked if we were thinking about using original music and I told him we absolutely would be. We nodded and smiled to one another and agreed to reconnect upon my return. I was excited to have the opportunity to work with Marvin, who is Dean of the Ernestine M. Raclin School of the Arts at Indiana University South Bend and was the first African-American composer commissioned to write a choral work for a Presidential Inauguration. His work, The City on the Hill, premiered at President Clinton’s 1993 Inauguration.

So, once we had a few scenes built, we shared them with Marvin. He brought one of his colleagues, Thom Limbert, to the meeting and they wound up collaborating on the score for several months. Once we had a solid rough cut, we turned it over to them so they could begin working on timing. Thanks to his understanding of modern technology, Thom created electronic versions of the composition, so we could actually hear the melody before engaging studio musicians. Once we had picture lock, Thom and Marvin brought professional musicians into the recording studio and conducted them while watching the video file, so that the synchronization would be perfect. It was fun to watch them work. Marvin told me early on that he’d had the beginnings of a song, which had been floating around in his head for years, that he felt would be perfect for the theme song. And so, that’s how ‘Song of Hope’ was born, which recently won the Bronze Award for Best Original Song at the 2016 Prestige Film Awards.

If you don't mind sharing, how did you fund this film?

The Hospice Foundation, which has been working with the Palliative Care Association of Uganda to expand palliative care throughout Uganda since 2008, provided all the funding for Road to Hope. The two organizations jointly established a fund to support orphaned child caregivers several years ago, so this film helps to shine a spotlight on that work. Any royalties generated by the film will be used to support that program.

Do you personally keep in touch with any of the children/ adults in the film? Do you follow their lives in any way?

Those are great questions. The short answer is “Yes” and “Yes.” As for the adults, Rose Kiwanuka and I speak regularly because of my work with the Hospice Foundation. Juli McGowan publishes a newsletter about her work at Kimbilio Hospice which I receive, so we occasionally exchange e-mails. Pastor Stanley was in the US for a visit back in 2015 and attended a private screening of the film before it was released. I’m Facebook friends with all of them and so I keep up with what they’re doing on a regular basis. With the exception of Shadrack, the children are a bit more difficult to stay in touch with. Shadrack is a regular Facebook poster and it’s fun to follow his journey. I have seen George a couple of times since we completed filming. I make a point of checking in on him whenever I am back in Uganda. He’s in boarding school near the village where he lived with his father and is being supported by our Road to Hope Fund.

What's next for Road to Hope and what is next for you?

Well, we’re getting close to the end of our run on the film festival circuit. The film has been an official selection in 49 festivals so far and won 13 awards with an additional 13 nominations. We’re at that point where we’d like to identify a distributor to work with. We’ve had a few inquiries, but nothing’s materialized that makes sense for us yet. As for me, I’ve got a couple of new projects on the horizon, including a documentary with a PBS affiliate and a web series through which we’ll release short stories about more children who are on their own roads to hope.

Is there anything you'd like to add?

Documentaries often get lost when they are viewed next to and compared against feature films. We’re honored to have been named LAFA’s Best Documentary and even more so, to have been named your Film of the Month. Thank you!

Learn more about Road to Hope:

Official Website: www.roadtohopefilm.com

Facebook: www.facebook.com/roadtohopefilm/ Twitter: www.twitter.com/roadtohopefilm